Hail to an Engineer Who Did It All

Legend has it that on January 12, 1828 during the construction of the Thames Tunnel in London, England, everything was fine—until it wasn’t. When the water started coming in there was little possibility for escape. This was the first project in the world to attempt to tunnel under a navigable waterway and it was a dangerous undertaking. Marc Brunel, chief engineer on the project, designed a tunneling shield that was being used for the first time, but the risks were still massive. The bed under the Thames River was a loose mix of rubble and clay and the likelihood of cave-ins was acute. The workers also had to deal with filthy sewage-laden water seeping into the tunnel at all times, methane gas emissions from the city’s floating garbage and other poor conditions.

On January 12 with the excavated area full of men, the tunnel flooded. The shield was the technological marvel of the day, but it wasn’t enough. The six men who tried to escape through the main exit died. The chief engineer’s son and main subject of this article, Isambard Kingdom (I.K.) Brunel, barely survived when he ran for a locked exit and someone miraculously opened the door just in time. The first tunnel ever to be built under a navigable waterway was eventually completed in 1841 after several periods where work completely stopped. Today that tunnel is still in use as part of the London Overground railway network. This article is about I.K. Brunel, the engineer who narrowly escaped death on Jan. 12, 1828. Shortly after he recovered, Brunel entered a competition that would culminate in the design and construction of the longest suspension bridge yet in history. The construction of the Clifton Suspension Bridge, still in service today with 4 million travelers annually, is where this story begins. This article is about a man considered by many to be one of the most influential mechanical and civil engineers of the Industrial Revolution.

Who is This Visionary Engineer of 19th Century Industrial England?

You wouldn’t believe all of the influential projects Brunel had a hand in. In England he is considered second only to Winston Churchill as the most influential person in U.K. history. Brunel became involved in railway projects early in his career and engineered and built bridges, stations and other elements of railroad infrastructure. Following his appointment as chief engineer of the Great Western Railway in 1833, he quickly became involved in developing what would become one of the wonders of Victorian England. He surveyed the route from London to Bristol and designed and built box tunnels and viaducts, most notably the historic Wharncliffe Viaduct, to cross stretches of wetlands. He had a vision to create one continuous passage of travel from London, England to New York, New York. Passengers would buy one ticket at Paddington station in London and be able to travel, first by rail, then by steamship, via the Great Western Steamship, all the way to the United States.

Wharncliffe Viaduct built in 1838 to take the Great Western Railway over the valley of the River Brent.

Brunel Tackles the Design of Steamships

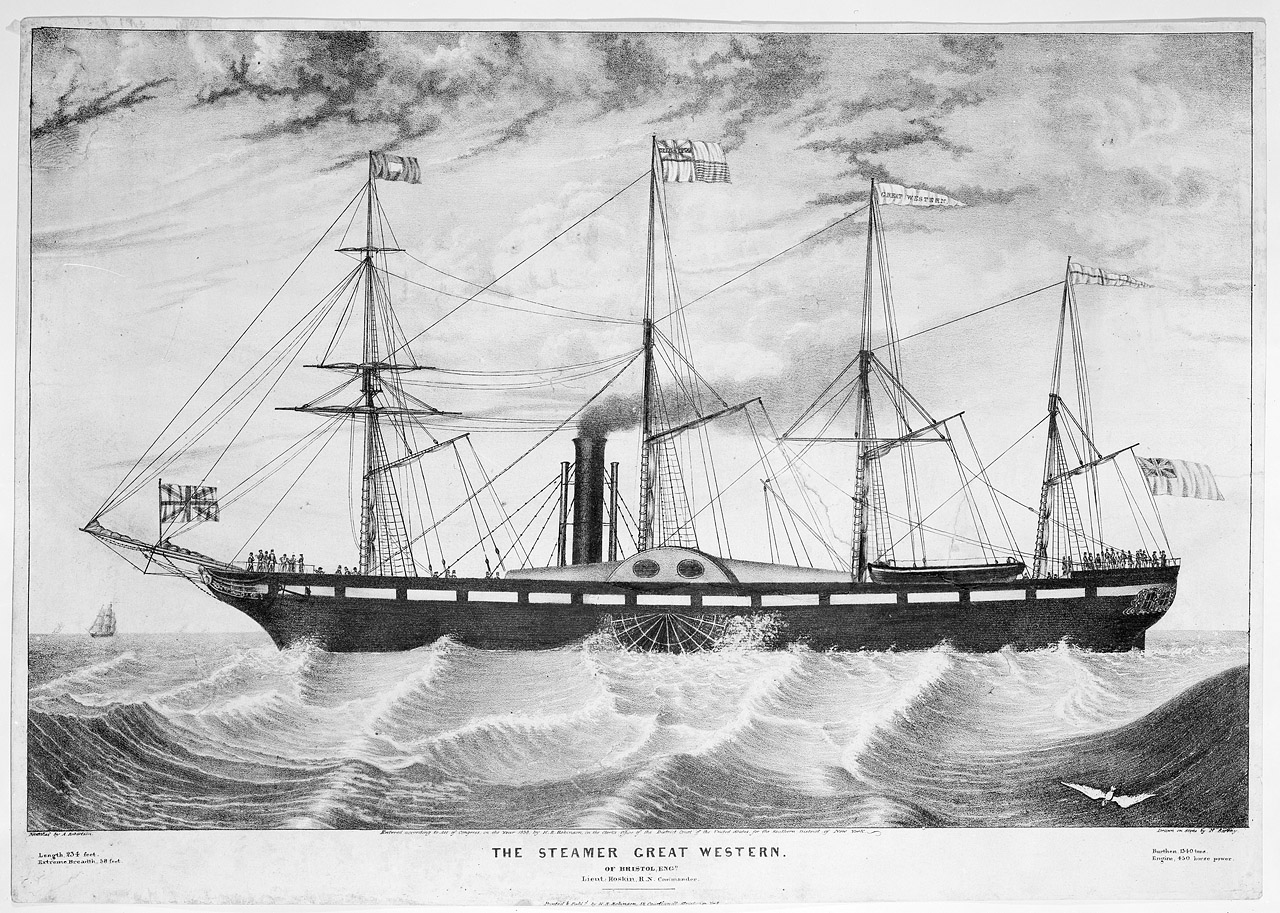

The Great Western Steamship Company was started with the purpose of realizing Brunel’s vision to create one continuous passage of travel, first by rail and then by sea. Brunel encountered much criticism that ocean travel by steam was impractical in view of the volume of coal that would be necessary to make the voyage. Brunel ultimately concluded that a larger ship would need proportionately less fuel than a smaller ship and set out to design his first steamship, the Great Western. When the Great Western was built it was the longest steamship yet designed at over 236 feet; in the end, the ship’s design proved commercially durable. The ship made 64 transatlantic crossings between 1838 and 1846. Brunel followed up with a design for a six-bladed propeller ship, the 322-foot Great Britain. This ship became the first modern ship built with metal, complete with iron hull and propeller. The Great Eastern was yet another remarkable design at over 700 feet and the capacity to transport 4000 passengers, but it was never used for passenger-travel. Rather, the ship was used for laying telegraphic cable and was responsible for placing the first transatlantic telegraph line.

A lithograph depicting the ‘Great Western’, which was the first purpose-built transatlantic steamship.

A Medical Clinic in a Time of Need

When Florence Nightingale pleaded with the British Government to provide a solution for injured men at the frontlines of the Crimean War in 1854, Brunel’s ideas would once again save the day. Brunel designed pre-fabricated hospitals to be shipped and set up in the Crimea; Nightingale later referred to these clinics as “those magnificent huts.” A heavy smoker who developed Bright’s disease early in life, Brunel had a stroke in 1859 and died at the age of 53.

Renkioi Hospital, a prefabricated building, designed by I. K. Brunel as a British Army military hospital for use during the Crimean War.

Brunel was nothing short of amazing in the variety and scale of work that he did. A true engineer as willing to dabble with steamship design as the construction of bridges and portable medical clinics, he achieved fame at an early age. He was hands-on all the time. A year or so before his death and during the course of making repairs, Brunel nearly died in a boiler-room fire on one of his steam-ships. Most importantly, Brunel helped build the infrastructure of cities when cities were just beginning to modernize. His work still stands in many parts of England and stays strong under the pressures of today’s vehicular traffic. Hail to the engineer who did it all.

Also Read: The Lesser Known Engineer: Nikola Tesla