Tales in Geography: John Wesley Powell Rides the Colorado (Part 1)

“We are three quarters of a mile in the depths of the earth, and the great river shrinks into insignificance as it dashes its angry waves against the walls and cliffs that rise to the world above… We have an unknown distance yet to run, an unknown river to explore. What falls there are, we know not; what rocks beset the channel, we know not; what walls rise over the river, we know not. Ah, well! We may conjecture many things. The men talk as cheerfully as ever; jests are bandied about freely this morning; but to me the cheer is somber and the jests are ghastly.” From the journal of John Wesley Powell as he describes his historic trip into the Grand Canyon.

(Powell, 1895, p. 157)

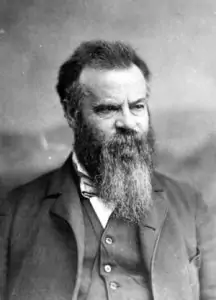

John Wesley Powell was an uncompromising and principled scientist, explorer and leader. Born in 1834 in New York, his family moved to Ohio and then, in 1845, to Wisconsin. Powell was only 12 when he began to manage the family’s farm. Constantly reading and exploring the nearby forests and creeks in his spare time, he collected rocks, Native American artifacts, shells and fossils, and studied plant and animal life as well. Anything that sparked his interest, he collected, preserved, and catalogued. Always yearning to explore, he made solo trips down the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers as a teenager. At the age of 15 he left home to go to school and live life on his own, ultimately settling in Janesville, Wisconsin.

Only two years later, Powell became a schoolmaster. His ever-curious spirit led him to university and to more exploratory trips. His collection of reptiles, minerals and fauna and his interest in geological formations continued to grow as did his urge to explore unknown landscapes. This post is one of a two-part series on Powell’s role in shaping history on the great American frontier. Part I of this post is dedicated to Powell’s beginnings as an explorer and mapmaker and revisits his famous trip down the Colorado River. The second part in this series will look at Powell’s work at the USGS (United States Geological Survey) and his prophetic ideas on land development and western water issues.

Early Signs of Leadership

Powell emerged from the Civil War an established leader. Notwithstanding the loss of an arm at the Battle of Shiloh, Captain Powell continued to serve the Union Army in various capacities, supervising the construction of bridges and trenches and training African American troops. All who served with him noted his masterful leadership skills as well as his ability to inspire and motivate. Honorably discharged in 1865, Powell taught at Illinois Wesleyan and then at Illinois State Normal. His restless, adventurous spirit also pulled him West; great adventures in the Rockies lay ahead.

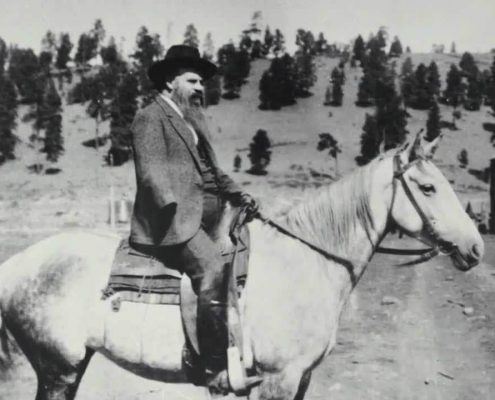

A Trial Run in the Mountains

In 1866, Powell managed to get funds for scientific equipment, rations and other resources from Washington D.C. to undertake a preliminary expedition into the Rockies. This investigative trip would give him an opportunity to learn how to handle equipment in risky situations, how to manage mountainous terrain with one arm, as well as how to lead a team of scientists and explorers. All of this knowledge would help him with his first large-scale expedition into the Grand Canyon. It was during this expedition that he climbed Pike’s Peak with his wife, Emma, establishing her as the first woman to reach the celebrated summit.

Whirlpools, Rocks and Unknown Water

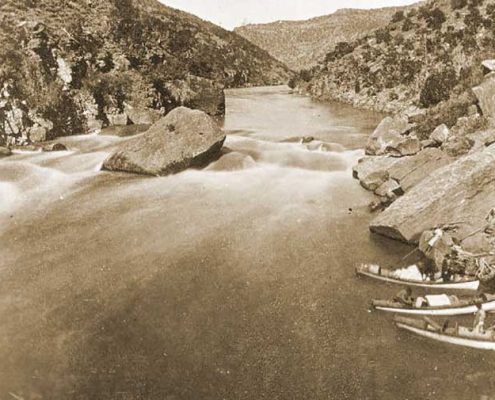

With four boats built especially for the voyage (one with a chair strapped to the center for Powell) and a team of nine other adventurers, Powell set out to ride the Colorado River in 1869. This trip is considered the first of its kind, as no other European had yet charted the course of the Green and Colorado Rivers through the Grand Canyon. Even with Powell’s careful navigational planning, the group encountered plenty of challenges. From drops of 30 feet or more down waterfalls, to being trapped in whirlpool torrents and dashed against black rocks, the small fleet of boats barely emerged in tact. One boat, the No Name, was destroyed along with a third of the supplies, scientific equipment and other gear before the group even reached the mouth of the Grand Canyon. During the remaining days of the trip, three men would leave the group out of fear and exhaustion. The remaining boats and men would experience treacherous rapids, the challenges of towering three-thousand-foot Canyon walls (which Powell referred to at times as a “granite prison”), and awesome landscapes. The group would emerge one thousand miles and 100 days later weary, but exhilarated. When the ragged group finally left the Canyon, Powell writes: “(T)he river rolls by us in silent majesty; the quiet of the camp is sweet; our joy is almost ecstasy.”

Men Who Surveyed the West

The Powell expedition took place during a time when surveying efforts were already underway through much of the West. Josiah Whitney surveyed the Sierra Mountains for the State of California and Clarence King had been hired by the U.S. War Department to survey and map a 100-mile stretch of territory for a proposed railroad line. Lieutenant George Wheeler explored southern deserts to establish U.S. supply routes. Ferdinand Hayden, as head of the United States Geological Survey of the Territories, was charged with uncovering information about coal and other minerals. Powell joined these efforts to map, describe and catalogue the West.

Powell’s Survey of the Colorado River Gorge

Congress funded Powell’s second expedition to the Colorado River in order to produce an official survey and add to the growing body of geographic and geologic information on western lands. Powell had other goals as well; he intended to not only map the area and perform more scientific experiments, but to bring back photographic images of the wild and unknown landscape. Towards this end, Powell brought along elaborate and heavy photography equipment, which had to be carried up and down steep rock walls by his men. But the resulting images turned out to be historically significant. These photographs now serve as the first set of panoramic shots of the Grand Canyon ever taken.

Because this second expedition was better prepared with supplies, the men were able to move along the river slowly, recording measurements and observations and producing new maps. Rivers that had been unrecorded were noted, newly discovered mountain ranges were named and mapped. The second expedition came to an early end in 1872, but the Grand Canyon continued to be mapped by Powell’s team in the years that followed.

Modern United States Geological Survey (USGS) Takes Shape

Once established in Washington DC, Powell argued that the government-sponsored survey work of Wheeler, Hayden and King should be combined into one set of maps. This initiative marked the creation in 1879 of one major agency to oversee these kinds of projects, the USGS. Powell became director of USGS in 1881; one of his primary goals was to use his position to study the West and the region’s water resources.

Powell’s Insight into Modern Water Issues

Did I mention Powell was a remarkable individual? His curiosity about the land, his leadership abilities and his drive to learn and explore set him apart, but he was also singular in his philosophy about land development. Powell’s Report, The Lands of the Arid Region of the United States, published in 1878, underlined that water was key to the success of all western land ventures. This seems obvious to us now in view of modern-day water conflicts, but at the time this indisputable truth went largely unrecognized. Powell discouraged land development in the West to the degree it took place without an understanding of the underlying water supply. As we’ll see in a future post, this position would prove unpopular with key business interests and marked the decline of Powell’s career. Powell’s work at the USGS and his controversial ideas about land development will be explored in Part II of this post.

“The gorge is black and narrow below, red and gray and flaring above, with crags and angular projections on the walls, which, cut in many places by side canyons, seem to be a vast wilderness of rocks. Down in these grand, gloomy depths we glide, ever listening, for the mad waters keep up their roar; ever watching, ever peering ahead, for the narrow canyon is winding and the river is closed in so that we can see but a few hundred yards, and what there may be below we know not…”

(Powell, 1895, pg. 161).

Also Read: Tales in Geography: John Wesley Powell at the Helm of the USGS (Part 2)

Bibliography:

- Worster, Donald (2001). A River Running West: The Life of John Wesley Powell, New York, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Powell, John Wesley (1895). The Exploration of the Colorado River and Its Canyons, Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society.